Adversarial Explanations

As noted in our introduction, XAI can be used to motivate and direct the design of models in an effort to maximize trust in the underlying model: it "breaks down the black box." Adversarial Artificial Intelligence, on the other hand, is a field that aims to figure out weaknesses in AI classification. By finding how a machine learning model can be exploited, it "causes the black box to break down." Both of these approaches to AI share a common goal: to construct models that are more robust against variations in data, biases, and even active exploitation.

As such, we in the XAI capstone project have partnered with Jonas Bartels, Alice Cutter, Sriya Konda, Yuxin Lin, Sky Lu, and Tingjun Tu of Carleton College's Adversarial Artificial Intelligence capstone project (project description) to bring you Adversarial Explanations: an Exploration and Exploitation of Machine Thought. In this section, we will present three examples of adversarial attacks on the ResNet50 image classifier, a deeper version of our ResNet18 model. All attacks are carried out through black-box methods, meaning that they do not have access to any parts of the model, and all explanations are model-agnostic, meaning that they do not require a specific architecture.

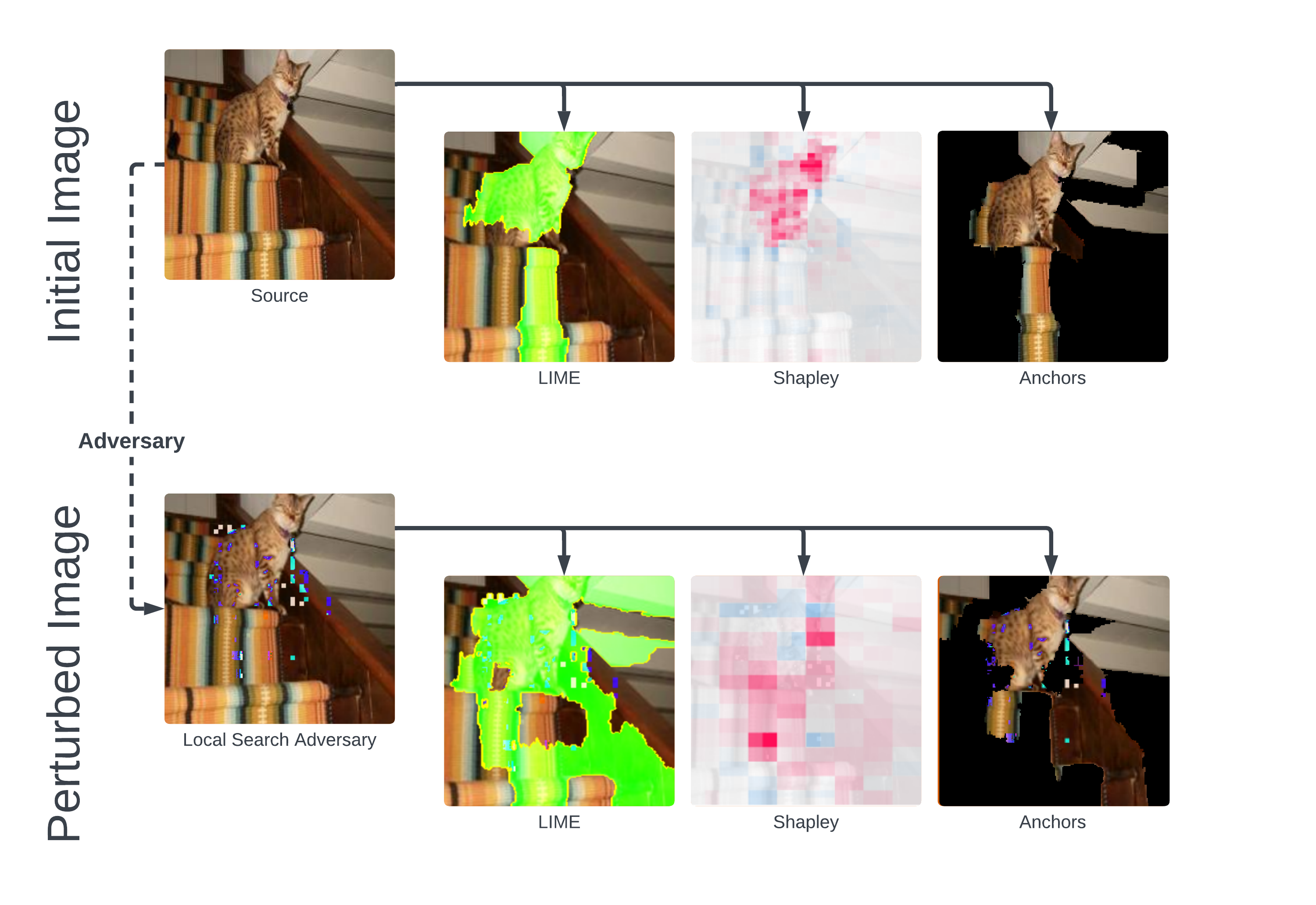

Local Search Adversary

The Local Search adversary utilizes the concept of greedy local search. It iteratively selects a small set of pixels to perturb that eventually would cause misclassification by a deep neural network without using any gradient information.

- Tingjun Tu, An Exploration of Adversarial Attacks on Image Classifiers

Before perturbation, our classifier correctly predicts that this is a Bengal cat with confidence. All techniques agree that the model looked at the area immediately around the cat to classify it as such. However, LIME and Anchors propose that our model also focuses a portion of the stairway to achieve this result, to which Shapley does not agree.

After perturbation, our model becomes much more hectic, producing a prediction of “altar.” Each technique confirms this messiness, as we can see that the model must now look at more than half of the image to find a modicum of justification for this prediction. This hectic nature is most likely due to an utter lack of confidence, which is displayed through Shapley values: although it is not in these images, the deepest red on this graph only adds confidence to the model from base, while each red area in the original image adds . Starved for foreground artifacts by LSA's pixel-injections, the machine learning model seems to search elsewhere for any possible indication of class; therefore, upon finding the cat's sloping surroundings, it predicts "altar."

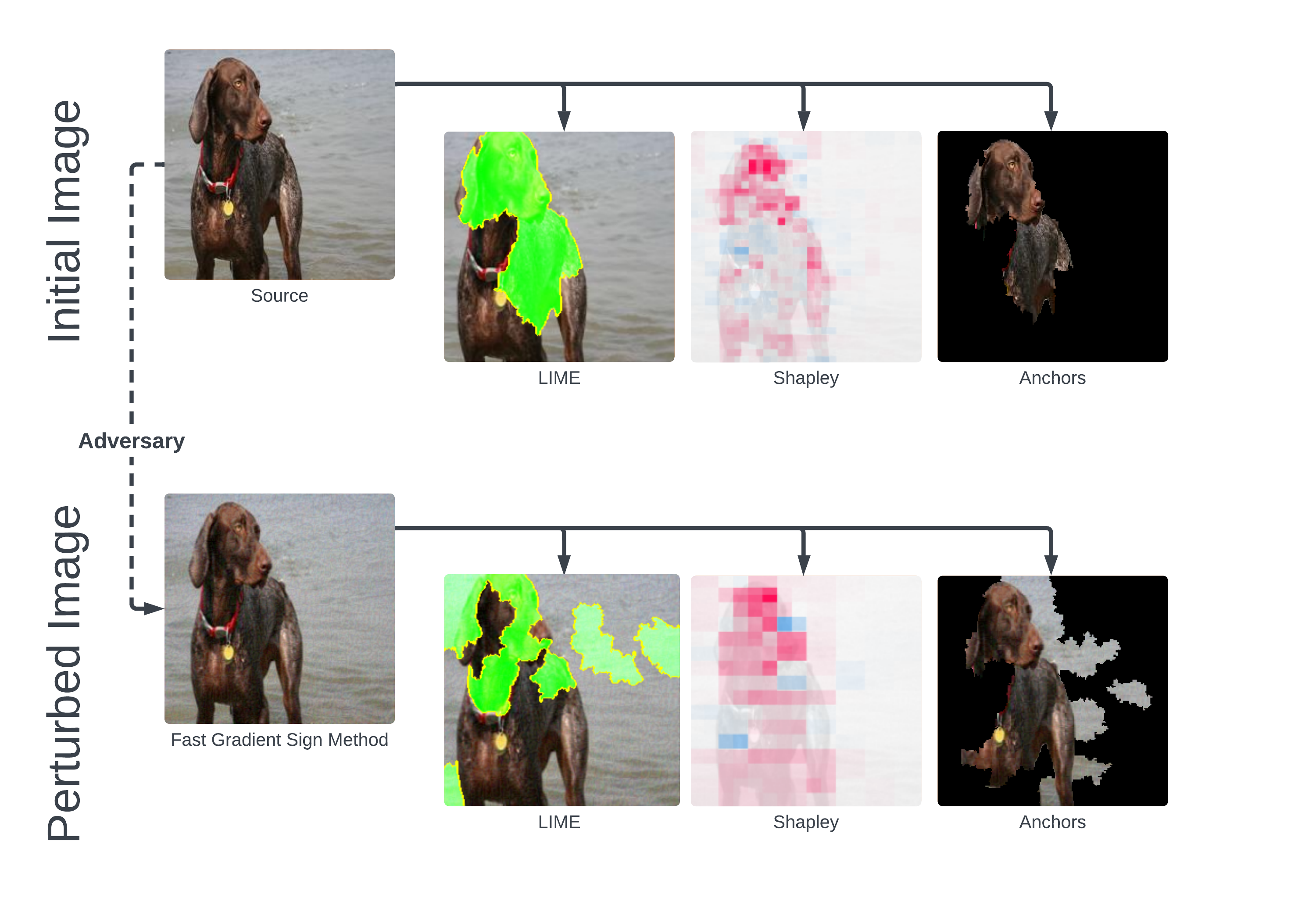

Fast Gradient Sign Method (FSGM)

FGSM uses the gradient of a loss function with respect to the input data to perturb each pixel in the direction that lowers the confidence of the correct prediction by a distance .

- Jonas Bartels, An Exploration of Adversarial Attacks on Image Classifiers

Pre-adversary, the model correctly predicts that this is a German Shorthair Pointer with 89.4% confidence. All explanations seem to agree that the dog itself is the point of focus. The Shapley values argue that our model looks for more specific parts of the dog, such as its face and legs, while more ambiguous parts of the body are unfavorably considered.

Here, the attack causes our German Shorthaired Pointer to be misclassified as a Vizsla, a similar dog breed. None of the explanations here are able to agree on the model’s decision. First, LIME claims that our model looks to the head of the dog, while Anchors and Shapley values argue that most if not all of the dog is observed in the prediction. From here, LIME and Anchors agree that some portion of the background is present in the prediction, while Shapley values argue that the model predicts almost exclusively on the dog’s main body. Perhaps there are a disproportionate number of Vizsla dog images with similar backgrounds, or perhaps the simple visual similarities between the two caused this mix-up.

Projected Gradient Descent

Projected Gradient Descent calculates the gradient of loss for an input image and applies it as a perturbation to the image over a course of small steps, modifying hyperparameters to keep the image looking as normal as possible.

- Sriya Konda, An Exploration of Adversarial Attacks on Image Classifiers

This is our hardest image to break, as the model correctly classifies this Persian cat with 99.1% confidence. All three techniques portray the strength of its reasoning, as all highlight the face and upper body of the cat almost exclusively, with some background artifacts.

Although perturbation of this sample does not succeed in its reclassification, the confidence drops to 26.2%. Moreover, this modification has precipitated the most interesting explanations of these samples: Shapley values propose that the cat is still the focus of the model for this prediction (only adding per pixel at most), while LIME argues that the model must avail of the background to achieve this result. Finally, Anchors show no change in the input image. Due to this technique’s niche (see our Anchoring page), we can infer that since no data may be removed from the image, no anchors are present in the input, and thus no specific piece of the input may be identified as sufficient for the model to predict this class. Such a perturbation in this image may have obscured the cat just enough to lower the confidence score and to cause the model to begin to reach out; however, upon looking for other features, the austere red background may not have fit any of its other filters, disallowing alternate predictions.

Conclusion

While Adversarial AI can be used to strengthen models, when paired with explanations, we can more easily see why a model breaks and exactly when and why we should or should not trust its decisions. Similarly, Explainable AI can display potential biases in machine learning models, allowing architects to improve their robustness, but an explanation cannot account for exploitable biases that are not visible in the data, thus requiring an adversary to reveal holes in the machine's thought processes.

Adversarial AI and Explainable AI are a part of a rich ecosystem of model fortification, each of which fits a niche alone; however, these two methods combined are able to build a cycle of continuous improvement, that which will ultimately create a safer and more trustworthy model.

We are grateful the Adversarial AI group for making this collaboration possible, and we would like to extend special thanks to Alice Cutter and Tingjun Tu for working so closely with us.